The draft OECD pillar one proposals are complex and deal with

more difficulties and issues than any of us might individually

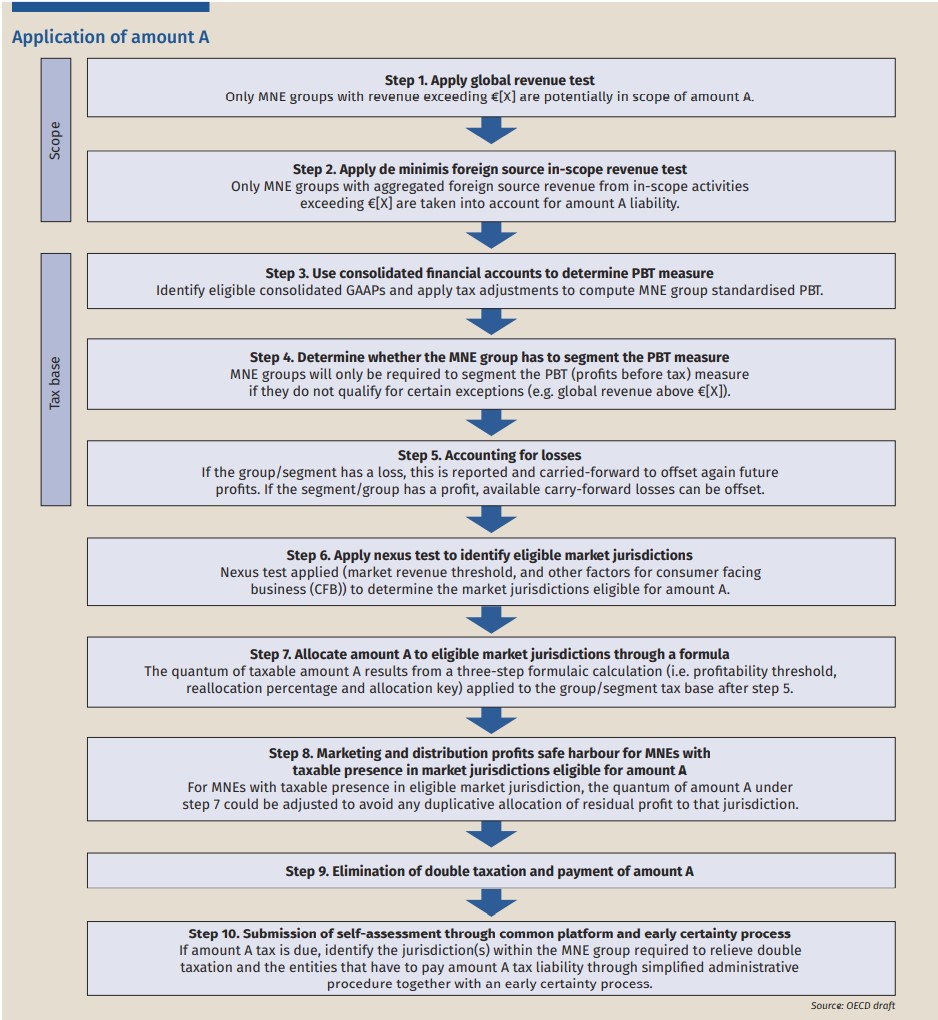

imagine. The proposals envisage eleven building blocks: six for

‘amount A’ (allocating taxing rights to the market jurisdictions);

two for ‘amount B’ (establishing fixed returns for marketing and

distribution activities); two concerning procedures to achieve ‘tax

certainty’; and a final building block covering implementation and

administration. If pillar one is to be implemented, impacted groups

have much to prepare for and little time to waste. However, with the

US currently outside the process and complexities mounting, some

might ask whether this whole journey is worth the effort.

As reported in Tax Journal (18 September 2020), leaks of the OECD’s ‘confidential’ proposals of 3 August 2020 to tax administrations have been doing the rounds of MNEs and advisory firms: 225 pages of detailed descriptions and analyses – bridging divergent interests and accommodating commercial complexities.

Eleven building blocks are identified. Six concern the new taxing right (‘amount A’), i.e. how to identify when an MNE should have an amount of residual profit reallocated among market countries; and how that should be identified, allocated and relieved. Two concern the fixed return for defined baseline marketing and distribution activities (‘amount B’), i.e. how to increase certainty on returns for ‘routine activities’. A further two relate to procedures to achieve ‘tax certainty’, and the final building block is on implementation and administration.

What, therefore, are the three Ps? Policy and Politics will ultimately determine whether pillar one comes into force. If so, the Practicalities of implementation will not be easy.

Policy

The OECD appears to have worked diligently to accommodate the widespread desire to allocate some of an MNE’s profits according to where its customers or users are. Yet important fundamental differences appear to remain. Is the purpose of amount A to ‘top up’ what a market territory is no longer generating from local activities (thanks to digitalisation) or is it a broader shift towards some taxing rights centring on the location of users

This question impacts on how residual losses might be relieved and when an amount A allocation is not required because of taxable income already in the territory.

It is one thing to justify who should receive an allocation, but quite another to determine where that same amount should be relieved and whether such relief should be by exemption or credit. This makes a real difference to whether ‘top up’ tax from a territory should be charged, and there is a further question of whether credit amount should be pooled.

The OECD appears to have listened to taxpayers’ desire for certainty; however, as mentioned below, there is a rather important catch.

Politics

There is no shrinking from the elephant in the room. Given that so many of those likely to be affected are US MNEs, can a new international system really be adopted that the US does not recognise? Many such MNEs have

regional headquarters in countries that remain part of the pillar one discussions, and the regime could conceivably apply by reducing their profits (the practicalities of regional structures are dealt with in Chapter 7).

However, the fear of anomalies and injustice may be a significant

barrier.

The draft may revive the nagging question of what this whole exercise is for. Put most simply, it is not clear which countries will be the losers in any reallocation

More broadly, the draft may revive the nagging question of what this whole exercise is for. Put most simply, it is not clear which countries will be the losers in any reallocation. The OECD may be banking on the expectation that countries will value the taxes reallocated to them more highly than the unilateral taxes they are giving up (as those reallocated taxes are more likely to be passed on to consumers). Countries may take positions on issues such as thresholds and allocation percentages based upon what most benefits them. There is a danger that under pillar one most countries will raise roughly the same amount of tax as before but in a highly expensive and more complex way.

Practicalities

For readers of this journal, the practicalities involved in implementing pillar one are likely to be by far the most significant issue. Such is the complexity of pillar one that it may take the combined minds of the tax profession a fair amount of time to fully hone a response. Perhaps due to this, the draft suggests the possibility of an entry threshold that will be reduced over time, meaning that only the very largest groups will fall within the regime initially. How that sits with the abolition of unilateral taxes is unclear. Some headline practical issues are set out below.

Scope/nexus

There are different rules for automated digital services (ADS) and consumer facing business (CFB). For ADS, there is a positive list of ADS activities, a negative list of non-ADS activities and a general definition. Financial services are excluded, although some are uneasy about the justifications for that decision. The specific model that companies fall into will impact how their profits are allocated, leading to further complexities around dual category or ‘bundled’ services. Impacted groups and their advisors will need to think carefully about their model, how allocation works and how that might evolve with their offering.

For CFBs, more than one party in the supply chain can have a relationship with a consumer, even if they do not transact directly with that consumer or take title to the product. Consensus is still required on what other engagement with the market is required to give sufficient nexus and whether there should be a presumption of presence above certain income thresholds. Significantly, no distinction is made between sales to businesses and to consumers where a product is sometimes used by consumers. In contrast, a distinction is made for some components where tracing the end consumer would be very difficult (for example, car tyres).

Lastly, the complexity and controversy on how to deal with pharma businesses is significant, with some heads of tax in affected groups privately pointing to a continued lack of recognition as to how markets work differently in different territories.

Sourcing

This section reads a bit more like legislation, and it brings to life the complexities associated with tracking.

For example, a location-based advert is allocated to the territory in which the user views it, whilst other adverts are based upon the user’s residence. There is significant guidance on other complex areas, such as identifying where a cloud purchaser uses services and how to deal with situations where VPNs are used.

Importantly, it is recognised that the sheer volume of transactions will require a systems and controls based approach to auditing. The increase in interactions with tax authorities may require affected companies to expand their skill sets and knowledge base in order to cope with these changes.

Tax base

There is an important discussion around the use and acceptance of different GAAPs, including whether standard adjustments are required for expenses typically disallowed and income from equity or equity accounting.

A compromise on segmented accounts has been suggested. Broadly, the proposal is to apply this to the largest groups, mainly those which already have segmented accounts. As with many of the proposals, however, the next step calls for further consideration (suggesting that it is some way off from the finished article).

The issue of losses seems to have exposed some philosophical divides. Firstly, it is not clear whether ‘a loss’ means less profit than the allocation threshold or an absolute loss. Additionally, there are questions about how long losses may be carried forward; what anti-avoidance rules are required; and whether and how to ensure parity between companies with volatile versus smooth profits.

These all reflect unresolved policy questions and give rise to uncertainty about implementation.

Allocation

A practical question exists as to which entities should be subject to the new tax. A hierarchy is proposed which starts with entities resident in territory. Tax could be charged to all profits in these entities, which might have an important knock on effect to dividend withholding tax and treasury management in some territories. A question remains unanswered as to whether amount A should be a ‘safe harbour’ for countries, allowing

them to top up taxable profits, or whether it should be a pure extra amount. There are related practical questions as to whether amount B profits should or should not count.

The most major unresolved question is what level of group profitability should lead to reallocation. Data suggests that including groups with relatively low profit margins may make the largest difference to the overall

amount available for reallocation. Importantly, there is a discussion on regional/jurisdictional variation, where more tax would be reallocated to jurisdictions/regions which are more profitable. Such differential allocation is seen as difficult, and the OECD is unclear about businesses operating on a regional basis.

Eliminating double taxation

If allocation seems complex, eliminating double taxation appears even more so. Numerous problems have been identified with regards to identifying the residual profit takers such as intra-group eliminations, different GAAP and different margins arising from the contrast between, say, buy/sell and licensing. A ‘four step’ approach is therefore proposed, which consists of:

- the qualitative identification of the residual profit takers;

- the application of ‘profitability tests’;

- assessing the connection with different markets; and

- pro-rata allocations where needed.

The more you look at each of these steps, the more complex they seem. Countries claiming amount A may be easier to identify than countries agreeing to relieve it. Additionally, there is the significance of the US remaining an outsider. Could some business either gain or lose from

the creation or collapse of regional structures?

It is also unclear how the divide between those territories favouring an exemption regime versus a credit regime will be resolved.

Amount B

Having a pre-agreed profit for routine marketing services, which could replace thousands of broadly similar TP studies, was seen as a prize to many groups. The reality still feels quite distant with unresolved questions about how to identify and segregate activities that are included, and whether there should be different regional/industry margins. It is hard to imagine that some countries, notorious for having an inflated view of the profit that should be allocated to routine activities, will allow a significant portion of their tax base to be eroded.

Certainty

It is hard not to sympathise with the OECD, which has been sensibly championing a better dispute prevention and resolution mechanism but must also manage countries’ concerns about loss of sovereignty. There is

a sensible focus on common documentation and the concept of a lead authority. Nevertheless, the reality of balancing competing countries’ interests was never going to be an easy problem to solve. The proposal for a review panel of representative tax authorities appears sensible in theory, but those authorities are each competing for their own slice of the revenue ‘pie’, so it seems optimistic to expect them to swiftly resolve what are undoubtedly complex and novel issues.

There is a sensible emphasis on prevention. After all, it is easier for countries to agree principles whilst their financial implications remain uncertain. However, anyone involved with negotiating a bilateral APA might harbour some scepticism as to whether the process will end up advancing certainty as opposed to merely bringing forward the inevitable audit. Whilst there may be sensible proposals on training and improving MAP processes, the sheer number of pages devoted to dispute prevention/

resolution tell their own story.

Those craving mandatory binding arbitration will spot the catch: the ‘innovative’ part of it is that both competent authorities who can’t agree must agree that the mechanism should be used. To many, that may not sound ‘mandatory’ at all.

And finally, the report also covers implementation issues, which will be of greater interest to legislators than users of the new provisions.

Standing back, where does this leave us?

Firstly, with a lot of new concepts and complexity. Secondly, with a dilemma. If there is still work to do and uncertainty on implementation, is it worth thinking through this complexity now? For those advising groups likely to be impacted, the answer is probably yes: there is simply too much to think about to risk falling behind. For others, though, this process may serve as more of a reminder that not every journey takes you to the

destination you imagined.